AR 1 – Arbeitsrecht 1 (Englische Version)

1 Scope of Labor Law and Basic Concepts

1.1 The Subject Matter Regulated by Labor Law

Labor law does not encompass all types of human work; for example, it does not regulate the work of self-employed professionals such as lawyers. Instead, labor law primarily governs the situation in which the majority of economically active individuals (approximately 90%) in our society earn their livelihood: by working as employees in the service of another, the employer. An employer can be a natural person (business owner), but more commonly, it is a legal entity under private law (such as a corporation or limited liability company), public law (federal, state, or municipal government), or a partnership (general or limited). Two fundamental aspects characterize this situation:

The employer retains the authority to define, within certain limits, the content, purpose, nature, manner of work, and working hours, and can issue instructions for these purposes. This is due, in part, to the fact that in a normally organized, specialized economic enterprise, an individual’s work is meaningful only in the context of other contributions, and thus someone must coordinate the integration of individual work into the overall work process through directives.

The immediate results of the work benefit the employer. Therefore, the work performed by the employee is for the benefit of another; it is service to someone else. The employer bears the responsibility and the economic risk for production and sales, ensuring that the work is economically effective. Since the employee cannot control the work process in which they are integrated and does not have a direct influence on the economic success of their work, it is not justifiable for the employee to bear the economic risk directly. This situation is prevalent in all countries with industrial modes of production, regardless of their economic and social order. It is not created by the legal system but is rather a pre-existing condition shaped by it.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, labor law also encounters living conditions influenced by the legal and social system. Therefore, the subject matter to be regulated by labor law is not entirely independent of the legal order; it is partially „legally generated.“ The integration of labor law in the new federal states of Germany was possible only with concurrent adaptation of other legal and economic conditions.

The legal and economic system of the Federal Republic is characterized by the principles of a market economy and private ownership of the means of production.

Under the principle of a market economy, economic processes (the nature and quantity of production and prices) are determined by market rules, particularly by supply and demand. The contrast to this is a planned economy (central economic planning), in which the state sets the decisive parameters, particularly the nature and quantity of production, as well as the prices, either directly or significantly influences them through approval requirements.

In a market economy, the wages and salaries of employees are also considered costs („human as a cost factor“). Who works under what conditions and for whom is subject to the private decisions of the parties involved (freedom to contract and structure). Demand for and supply of labor thus determine the compensation that can be paid or obtained. On the other hand, the state has no direct influence over who works in a specific company and what they earn there. To assess this situation fairly, it must be taken into account that it is essential for an individual employee to find a job to make a living, and for this purpose, there are typically only a few employers in the immediate vicinity. In contrast, the employer can decide not to employ individual employees, but usually has a much wider selection of potential candidates.

The individual employee is economically and socially weaker; therefore, when establishing the employment relationship, the employer typically has a bargaining advantage. If left solely to the play of supply and demand, it would be difficult for the individual employee to achieve reasonable working conditions, as the employer, for various reasons, is interested in keeping labor costs as low as possible, particularly for competitive reasons.

Private ownership of the means of production results in the situation where individuals who want to work but require physical tools (spaces, machinery, materials, vehicles) depend on another, who has control over these means and makes them available. Consequently, the employer, as the owner of the means of production, has the power to calculate the employee’s wages and salaries in a way that enables them to earn a profit from the value creation contributed by the employees. Since the means of production require capital investment—partially with their own funds, but to a large extent, with borrowed funds provided by banks—and since a portion of the profit is reinvested in capital, this forms the essential characteristic of the capitalist economic system.

The conflicting interests that need to be balanced are the focus of labor law:

- The employer aims to produce as cheaply as possible, preferring lower wages, while employees seek higher wages.

- Employers do not wish to pay wages without work, whereas employees expect compensation even when they cannot work.

- Employers desire the flexibility to reduce or replace personnel, while employees seek job security.

- Employees are concerned with safe equipment and facilities to prevent accidents, whereas employers may resist safety regulations that increase production costs or complexities.

- Employers seek broad authority to issue directives, especially on the company’s economic aspects, while employees are interested in limiting directive powers and participating in crucial decisions or making them themselves.

However, the principles of a market economy and private ownership of means of production do not solely determine our legal and social system. The fundamental constitutional decisions for democracy and a welfare state (Art. 20 Abs. 1 GG) also play a significant role in shaping this framework. They mandate a balance of the described conflicting interests.

The welfare state principle prevents unrestrained capitalism and free utilization of production capital because it would adversely affect the socially weaker individuals. It requires essential social safeguards, and the majority of the population demands further social protections, even beyond what is strictly necessary under the welfare state principle. Consequently, labor law is tasked with providing extensive protection to employees.

While the democracy principle initially applies only to the state sphere, it has political implications for the economy. It justifies demands for employee participation in companies, which restricts the owners‘ control over the means of production (Art. 14 Abs. 1 S. 2 and Abs. 2 GG).

To summarize, the life situation that labor law regulates can be described as follows: in an industrial society, most gainfully employed individuals are employees working for others (employers). They are subject to instructions and work for someone else’s benefit, without bearing the direct economic risks of their labor. In the Federal Republic of Germany, the integration of labor into the production process and compensation are generally subject to market-based rules, and ownership of the means of production is in the hands of business owners. These factors give rise to the conflicting interests that labor law addresses.

The principles of the welfare state, democracy, and resulting political movements, leading to the social market economy as the Federal Republic’s economic model, demand a balance of interests that particularly considers employees. Therefore, the purpose of labor law is to compensate for or alleviate the disadvantages faced by economically and socially disadvantaged employees in contractual negotiations and performance resulting from the market economy.

1.2 Scope of Labor Law Employees and Employers, Employment Contracts, and Employment Relationships

German labor law governs the legal relationships between individual employees and employers (individual labor law), as well as the relationships between employee and employer coalitions and the representation bodies of employees and the employer (collective labor law). Labor law originated as a means of protecting employees, and it continues to primarily serve the purpose of employee protection. Despite efforts and provisions outlined in the Unification Treaty to establish a labor code, there is still no comprehensive codification of labor law in place.

Regulations can be found in the following legal sources:

- European law

- Statutes

- Collective bargaining agreements for sectors and individual companies

- Works agreements and service agreements (public service)

- Individual employment contracts

It is important to note that judicial decisions, often referred to as „judge-made law,“ do not constitute a legal source as they are not legally binding. However, in practice, judge-made law plays a significant role in labor law, especially in areas that lack statutory regulation, such as labor dispute law.

1.3 The Concept of an Employee in the Legal Sense of Labor Law

The concept of an employee is fundamental to the scope of labor law. Labor law protections are only applicable to employees, and these protections for employees are quite extensive. Additionally, liability for causing damage in labor law is significantly limited compared to other contractual agreements. However, not every individual who provides labor or services to others through a private contractual relationship is considered an employee in the legal sense. The law does not provide a universally applicable definition of the term „employee,“ even though this term is used in various laws. According to the Federal Labor Court, the basic criteria are that the individual provides dependent and externally directed services to others under a private law contract in exchange for remuneration (Federal Labor Court ruling of August 20, 2003 – 5 AZR 610/02, NZA 2004, 39).

The first requirement for qualifying as an employee is that there must be a private contractual agreement between the employer and the employee. Therefore, the following individuals are not considered employees:

- Civil servants, judges, and soldiers. Their public law service relationships are established by administrative acts and regulated by specific laws. However, workers and employees in the public sector are considered employees.

- Inmates, individuals in security detention, and others working in an institution under a public law power relationship.

- Spouses and children who provide labor in the household or business of their spouse or parents. An exception applies when the extent of their involvement goes beyond family law obligations, in which case an implied employment contract may exist in individual cases.

- Individuals who act as members of an association and have sufficient protection through their membership rights.

- The legal relationship between employable individuals receiving assistance and the service provider based on § 16(3) sentence 2 of the Social Security Code II (so-called „one-euro job“) is not an employment relationship but rather a public law relationship. Therefore, the assistance recipient is not entitled to remuneration (Federal Labor Court judgment of September 26, 2007 – 5 AZR 857/06).

For a long time, the employment contract between the employer and the employee was considered a subset of the service contract under § 611 of the German Civil Code (BGB), even though it was not explicitly mentioned there. It was only in 2017 that the legislator introduced the employment contract as a distinct type of contract, specified under § 611a BGB.

In a service contract, the service provider commits to providing the promised services in exchange for remuneration. This allows the employment contract to be distinguished from contracts for specific work and agency contracts:

- Unlike an employment contract between an employee and employer, in a contract for specific work (§ 631 BGB), the contractor owes a specific result. How the contractor achieves this result can be self-determined. In contrast, the employee only needs to provide their labor, and the employer determines the time, method, and place of work.

- In an agency contract (§ 662 BGB), the agent works without remuneration, while the service provider can request remuneration.

Distinguishing between an employment contract and an independent service contract is not always straightforward. § 84(1) sentence 2 of the Commercial Code (HGB) provides a guideline for differentiating self-employed commercial agents from employees. According to this provision, an individual is considered self-employed if they can largely determine the organization of their work and their working hours freely. In contrast, an employee is someone who is personally dependent.

The employment relationship differs from that of an independent contractor based on the degree of personal dependence the service provider has. Economic dependence is neither required nor sufficient to establish an employment relationship. Employees are integrated into the employer’s work organization, primarily through their subordination to the employer’s instructions. In particular, a work relationship exists for employees who are unable to freely shape their work activities or determine their working hours.

Examples of individuals considered employees include:

- Field sales representatives who have relative freedom in choosing their work locations, usually within specific geographic areas.

- Employees with flexible working hours who can determine their individual working hours to some extent.

- Telecommuting employees who can perform their work from home using a computer.

- Chief physicians, who, while mainly free in their profession, are integrated into the organization of hospital operations.

Examples of individuals not considered employees include:

- Partners in partnerships, who are not employees and provide services to promote the partnership’s goals based on the partnership agreement. They are generally not personally dependent, as they possess partnership shares and are involved in decision-making within the partnership.

- Legal entities that act through their officers (managing directors of a GmbH or board members of a stock corporation). The officers or members of governing bodies perform employer functions for the company. As such, they are generally not considered employees but rather engage in an independent service relationship with the company. If an employee is appointed as a managing director, they may lose their employee status in case of doubt.

In determining whether an individual is an employee or a self-employed contractor, various criteria may need to be considered. In some cases, employers may refer to employees as freelancers to circumvent labor law protections and social insurance obligations. This misclassification can lead to individuals being deemed „bogus“ self-employed. However, the designation used in the contract is not decisive. Rather, the actual implementation of the contract is more important.

For example, if a law firm owner assigns cases to a lawyer who must work in external law firm offices during specified working hours, the lawyer may be classified as an employee due to their significant dependence, despite being labeled as a freelancer in the contract.

In some cases, it may be necessary to consider additional criteria to differentiate between an employment contract and an independent service contract. Some factors that support the classification of an individual as an employee include:

- The absence of personal capital investment

- Lack of an independent work organization

- No utilization of their own auxiliary personnel

1.4 Concept of the Employer

The question of who constitutes an employer can be answered swiftly and straightforwardly. There is no statutory definition of the term. An employer is any person or institution that employs at least one employee. The status of an employer is primarily shaped by the right of direction, through which the employer can more precisely determine the concrete obligations of the employee regarding the nature, place, and time of work.

An employer can be:

- A natural person (e.g., sole proprietor, private individual).

- A legal entity under private law (e.g., a stock corporation, limited liability company, incorporated association).

- A legal entity under public law (e.g., federal, state, municipality, religious community).

- An unincorporated association (non-incorporated association, civil law partnership).

- A partnership (general or limited partnership).

In the Works Constitution Act, the concept of the employer is used in two ways: on one hand, the employer is the contractual partner of the employee, and on the other hand, the employer is an organ of works constitution. In this context, the terms „entrepreneur“ and „employer“ are interchangeable and merely refer to different legal relationships, functions, and activities of the same person.

1.5 Applicability of Labor Law to Specific Groups of Individuals

1.5.1 Persons Similar to Employees

A person similar to an employee is someone who, like an employee, is economically dependent on a client but is not personally dependent like an employee due to the lack of integration into a company’s organization and the essentially free determination of their time. A person similar to an employee is a self-employed entrepreneur. The distinction from employees is thus based on the degree of personal dependence. Persons similar to employees are not as personally dependent as employees because of their lack of integration into a company’s organization and their essentially free determination of time. The feature of economic dependence replaces personal dependence and being bound by instructions. Additionally, the economically dependent individual must, in terms of their overall social position, be similarly in need of social protection as an employee. The aforementioned features primarily apply to homeworkers and sales representatives who can only work for one employer due to contractual agreements or the scope of their activities. Someone who, in a service or work contract or a similar legal relationship, is economically dependent and provides services or works personally and primarily without the involvement of employees is thus similarly in need of social protection as an employee.

Additional examples of persons similar to employees include:

- Artists

- Writers

- Employees of audio and television broadcasting, as well as

- Sales representatives, especially single-company representatives with low income. However, they are considered employees if, on average, they have not earned more than 1,000.00 euros per month based on the employment relationship, including commissions and compensation for expenses incurred in the regular course of business, during the last six months of the employment relationship (Federal Labor Court, decision of October 24, 2002 – 6 AZR 632/00, NZA 2003, 668).

Certain provisions of labor law are applicable to the contractual relationships between an entrepreneur and a person similar to an employee due to their need for social protection. However, the applicability of individual labor laws or legal regulations to other types of relationships apart from employment relationships must be expressly specified on a case-by-case basis (Federal Labor Court, decision of May 8, 2007 – 9 AZR 777/06, BB 2007, 2298).

Examples of corresponding legal regulations include:

- According to § 5 (1) of the Labor Court Act (Arbeitsgerichtsgesetz), persons similar to employees have access to labor courts.

- They are also entitled to the legal minimum vacation of 24 working days, as stated in § 2, sentence 2 of the Federal Vacation Act (Bundesurlaubsgesetz).

- Based on various state laws, persons similar to employees may also be entitled to educational leave.

- According to § 12a of the Collective Agreement Act (Tarifvertragsgesetz), the employment conditions of persons similar to employees can be regulated by collective agreement. Such collective agreements primarily exist for freelance employees in the journalism sector at broadcasting companies.

- The contractual relationships of sales representatives who work exclusively for one employer can also be subject to minimum working conditions as per § 92a of the Commercial Code (Handelsgesetzbuch).

However, the extended notice periods in accordance with § 622 of the Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, BGB) also apply to so-called „persons similar to employees“ (Regional Labor Court of Cologne, decision of May 29, 2006 – 14 (5) Sa 1343/05).

The Employee Protection Act and the special termination provisions in § 9 of the Maternity Protection Act and the Ninth Book of the Social Code (Sozialgesetzbuch, SGB IX) do not apply. The Continued Remuneration Act (Entgeltfortzahlungsgesetz, EFZG), which regulates the right to payment in cases of illness-related incapacity to work and on public holidays, is also not applicable to persons similar to self-employed workers. Since persons similar to employees are not covered by the Works Constitution Act (Betriebsverfassungsgesetz, BetrVG), the works council does not need to be consulted in the case of corresponding terminations. However, the employer is obliged to regularly inform the works council about the use of other individuals working in the company but not in an employment relationship (§ 80 Abs. 2 Satz 1 BetrVG), such as freelance workers and persons similar to employees.

1.5.2 Individuals Engaged in Homework

A homeworker is someone who works in a self-selected place of work on behalf of others for remuneration. An implicit characteristic is that the work is of a straightforward nature. This can also include simple clerical work as homework. A defining feature of homework is that the homeworker is economically dependent on their client but remains personally independent. They can freely determine their working hours and the extent of their work. Therefore, in the legal context of labor, they are not considered employees. Labor law does not, therefore, generally apply to homework arrangements. Nevertheless, it is always necessary to examine the specific labor laws or collective agreements to determine whether and to what extent they also apply to homework arrangements.

Examples of regulations that equate homeworkers with employees:

- Homeworkers are included in the definition of employees under the Works Constitution Act (Betriebsverfassungsgesetz) in accordance with § 5 (1) sentence 2 BetrVG.

- For disputes between the client and individuals engaged in homework, the labor court is competent, as per §§ 2, 5 (1) sentence 2 ArbGG.

- They are entitled to leave and holiday pay as per § 12 BUrlG.

- Homeworkers are subject to maternity protection laws according to § 1, 9 MuSchG.

- There is a right to homeworker supplements under § 10 EFZG.

- On holidays, remuneration must be continued according to § 11 EFZG.

- Job security for severely disabled homeworkers is covered by § 127 (2) SGB IX.

Individuals engaged in homework are additionally protected by the Home Work Act (Heimarbeitsgesetz, HAG) due to their economic dependence. This includes provisions related to:

- Occupational safety, §§ 10, 11 HAG.

- Hazard protection, §§ 12 – 16a HAG.

- Wage regulations and wage protection, §§ 17 – 27 HAG.

- Job security according to §§ 29, 29a HAG.

To make a termination of a homeworker arrangement effective, proper consultation with the works council is mandatory under § 102 BetrVG, as homeworkers are part of the group protected by the Works Constitution Act.

1.6 The Employment Contract

The employment contract is a mutual agreement through which the employee commits to providing the promised work, and the employer commits to providing the agreed-upon compensation (wage) for that work. The initial stages of forming the contract create a special relationship between the parties, which leads to specific obligations such as obligations to provide information, care, and confidentiality.

The principle of contract freedom generally applies to the conclusion of employment contracts. This means that parties are free to decide whether, with whom, with what content, and in what form they want to enter into the contract. Employment contracts can typically be concluded informally. However, since the enactment of the Employment Proof Act (Nachweisgesetz), employees have the right to written documentation of the essential terms and conditions applicable to them. Nevertheless, a formal requirement can be established, for example, through a works agreement or a collective agreement.

1.7 Concept of the Employment Relationship

An employment relationship is a legal relationship that arises from a legally effective employment contract between an employee and an employer, essentially focusing on the exchange of work performance and remuneration. An employment relationship exists from the moment when there is a legal obligation for the complete or partial execution of the employment contract.

Case Study „Commencement of the Employment Relationship“:

Employer T and caregiver A enter into a contract on 02/01/2022, in which A is to begin work on 04/01/2022. A falls ill on 03/30/2022 and is unable to work for 4 weeks. Is she entitled to continued wage payment during her illness?

Solution:

A is not entitled to continued wage payment during illness. Although there is an effective employment contract, an employment relationship only exists starting on 04/01/2022. Additionally, the performance of the employment relationship through work commencement is a prerequisite for wage continuation during illness.

1.8 Manual Workers and Salaried Employees

Distinguishing between manual workers and salaried employees varies between social security law and labor law. In social security law, there is no longer a clear separation between manual workers and salaried employees. In labor law, although the division of employees into the categories of manual workers and salaried employees is partly still defined in the law and especially in collective bargaining agreements, there are no longer any legal distinctions between these two groups in labor law, except for the legal concept of executive employees. Unequal treatment of manual workers and salaried employees without a justifiable reason is considered a violation of the principle of equality.

A manual worker is an employee who primarily earns their livelihood through physical labor. They provide their physical labor to an employer in exchange for compensation, which is typically referred to as wages. Manual workers are generally skilled laborers or other employees engaged in physically demanding work.

Salaried employees are employees who primarily perform intellectual (office-related, administrative, higher technical, predominantly managerial, or otherwise elevated) tasks. The remuneration for salaried employees is provided in the form of a salary, usually as a fixed monthly amount, in contrast to the hourly wages typically agreed upon for manual workers.

1.9 Executive Employees and Their Legal Status

In the legal definition according to § 5 (3) of the Works Constitution Act (BetrVG), the identity of executive employees is explicitly determined. According to this definition, an executive employee is someone who, based on their employment contract and their position in the company or establishment:

- Is authorized to independently hire and dismiss employees who work in the company or department (§ 5 (3) sentence 2 No. 1 BetrVG), or

- Holds general power of attorney or procuration, and the procuration is not insignificant in relation to the employer (§ 5 (3) sentence 2 No. 2 BetrVG), or

- Routinely performs other tasks that are essential for the existence and development of the company or establishment and require special experience and knowledge, either making decisions essentially free from instructions or significantly influencing decisions (§ 5 (3) sentence 2 No. 3 BetrVG).

Most commonly, these are referred to as senior non-union employees. A senior non-union employee is someone employed in a company where a collective bargaining agreement is in effect. However, the senior non-union employee enters into an individual employment contract with the employer. Their compensation exceeds the highest pay group of the relevant collective bargaining agreement. The defining characteristic of this group of salaried employees is that they have responsibilities and qualifications exceeding those required for the highest salary group under an applicable collective bargaining agreement. However, senior non-union employees are not automatically considered executive employees.

Executive employees have a unique legal status in several respects:

- The Works Constitution Act (BetrVG) does not apply to executive employees unless the BetrVG expressly provides otherwise. They have neither active nor passive voting rights in works council elections.

- The law regarding speaker committees (SprAuG) includes participation rights for executive employees.

- Although the Protection Against Unfair Dismissal Act (KSchG) applies, the criteria for justifying a termination are significantly more lenient. The employment relationship can be terminated upon the employer’s request with a severance payment during the protection against unfair dismissal process.

- Executive employees are exempt from the Working Hours Act (Arbeitszeitgesetz), but they are entitled to overtime pay if paid according to a collective bargaining agreement or slightly above it.

- For the effectiveness of a fixed-term employment contract, it is generally sufficient for executive employees to receive financial compensation upon termination.

- Executive employees are not subject to collective bargaining agreements.

- When terminating an executive employee, the works council is only required to be informed, and a failure to meet this obligation does not affect the termination.

2 Legal Structure of Labor Law

Labor law is typically divided into individual labor law and collective labor law, according to its areas of regulation.

2.1 Individual Labor Law

Individual labor law pertains to the part of labor law that regulates the legal relationships between the employer and individual employees. It encompasses aspects such as the creation, content, disruptions, transfer, and termination of employment relationships.

Firstly, there are various laws that apply to all employees within their respective subject matter:

- Employment Protection Act (Kündigungsschutzgesetz or KSchG)

- General Equal Treatment Act (Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz or AGG)

- Working Time Act (Arbeitszeitgesetz)

- Continued Payment of Remuneration Act (Entgeltfortzahlungsgesetz or EFZG)

- Federal Vacation Act (Bundesurlaubsgesetz or BUrlG)

- Employment Confirmation Act (Nachweisgesetz or NachwG)

- Part-Time and Fixed-Term Employment Act (Teilzeit- und Befristungsgesetz or TzBfG)

- Commercial Code (Gewerbeordnung) – §§ 105 to 110 apply.

- Occupational Safety Act (Arbeitssicherheitsgesetz or ASiG)

- Workplace Protection Act (Arbeitsschutzgesetz or ArbSchG)

- Maternity Protection Act (Mutterschutzgesetz or MuSchG)

- Federal Parental Allowance and Parental Leave Act (Bundeselterngeld- und Elternzeitgesetz or BEEG)

- Youth Employment Protection Act (Jugendarbeitsschutzgesetz or JArbSchG)

- Social Code IX (Law for the Severely Disabled)

- Workplace Protection Act (Arbeitsplatzschutzgesetz or ArbPlSchG)

- Temporary Employment Act (Arbeitnehmerüberlassungsgesetz or AÜG)

- Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch or BGB)

- Nursing Time Act (Pflegezeitgesetz)

- Employee Invention Act (Arbeitnehmererfindungsgesetz or ArbNErfG)

Additionally, there are special laws that apply to specific groups of employees depending on the legal characteristics of the employer:

- Those who provide commercial services in commercial enterprises (the employer must be a merchant as defined by the German Commercial Code or HGB) are classified as commercial employees, and §§ 59 ff. HGB apply.

- Miners and mining employees are subject to special provisions under the Federal Mining Act (Bundesberggesetz), §§ 51 ff.

- Seafaring crew members are governed by the Seamen’s Act (Seemannsgesetz).

2.2 Collective Labor Law

Collective labor law relates to the law governing labor organizations (unions and employer associations) and workforce representation (works councils and staff councils). This includes labor disputes, collective agreements, the Works Constitution Act, and co-determination rights.

Collective labor law deals with legal relationships in which a group (hence the term „collective“) of employees is affected, rather than an individual employee. The term „collective“ can encompass various groups of people, including all employees in a company or establishment, or specific groups like all severely disabled employees. Well-known examples include labor dispute law, where labor unions and employer associations face each other, as well as legal relationships arising from collective agreements or works council elections. This field can be further divided into two major areas: „Collective Agreement Law“ and „Works Constitution Law.“

2.2.1 Collective Agreement Law

Collective autonomy is a constitutionally protected right of labor unions and employer associations, enabling them to independently negotiate collective agreements. Collective agreements are a significant source of employment conditions for many workers in Germany. A collective agreement is typically negotiated between labor unions and employer associations, and occasionally between labor unions and a single employer.

An agreed-upon collective agreement can also apply even if it has been declared generally binding in accordance with § 5 TVG (Collective Agreement Act). This is particularly important because a generally binding collective agreement applies even if an employer or employee is not affiliated with a labor union or an employer association, meaning all employers and employees within the agreement’s scope are bound by its terms. The Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs maintains a list of generally binding collective agreements on its website.

2.2.2 Works Constitution Law

Works constitution law governs the collaboration between the employer and the workforce of a company, represented by the elected works council. Works constitution law essentially regulates the intra-company relationship between the employer and the workforce.

A fundamental principle of the Works Constitution Act is the cooperative collaboration between the employer and the works council. This collaboration occurs in concert with labor unions and employer associations present in the company. The objective is to work for the benefit of the employees and the company.

Section 2 of the Works Constitution Act states:

„Employers and works councils must work together in a spirit of mutual trust and in cooperation with the labor unions and employer associations represented in the company in accordance with the applicable collective agreements.“

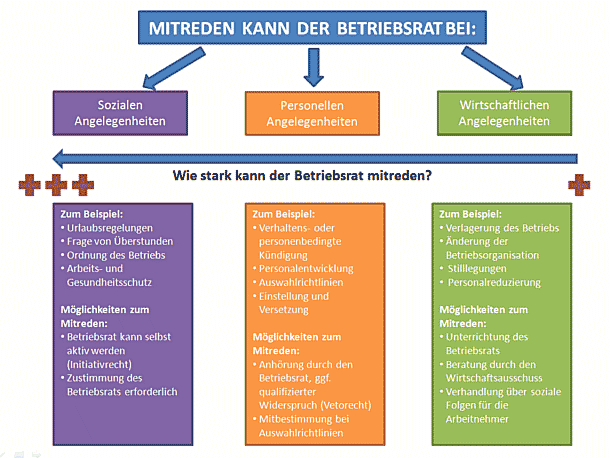

The works council plays a crucial role in this context. According to § 1 of the Works Constitution Act, companies with a usual minimum of five eligible voters, of whom three are eligible for election, must elect works councils. The works council is elected by the employees and is responsible for ensuring that the laws, regulations, collective agreements, and company agreements that benefit the employees are observed and implemented. It is also involved in social, personnel, and economic matters. These participation rights are divided into co-determination rights and participation rights.

The most important laws related to works constitution law include:

- § 9Abs. 3 of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz)

- Speaker Committee Act (Sprecherausschussgesetz or SprAuG)

- Codetermination Act (Mitbestimmungsgesetz or MitbestG)

- Montan Codetermination Act (Montan-Mitbestimmungsgesetz or MontanMitbestG)

- Codetermination Supplementary Act (Mitbestimmungsergänzungsgesetz or MitbestErgG)

3 Sources of Labor Law and Design Factors, and Their Hierarchy

Despite some efforts and the provision in the Unification Treaty to create a unified labor code, there is still no uniform codification of labor law. As a result, the content of employment relationships can depend on various legal sources and design factors. Therefore, it is necessary to establish their hierarchy, which is as follows, from the highest to the lowest design factor:

- European Primary Law and Secondary Law

- German Constitutional Law

- Mandatory Labor Law Acts

- Collective Agreements

- Collective Agreements with Discretionary Labor Laws

- Works Agreements

- Employment Contracts (including general employment conditions, company practices, and the principle of equal treatment under labor law)

- Discretionary Labor Laws

- Employer’s Right of Direction

In principle, the higher-ranked regulation takes precedence over lower-ranked ones, a concept known as the hierarchy principle. However, the hierarchy principle does not apply when a lower-ranked basis of entitlement is more favorable to the employee, known as the principle of favorability. According to the principle of favorability, the lower-ranked regulation is applied when its content is more favorable to the employee. While the principle of favorability is legally stipulated only in § 4 (3) TVG, it is widely considered to be applicable throughout labor law.

Example:

According to a collective agreement, all employees are entitled to 30 days of annual leave. However, Employee A’s employment contract specifies 32 days of leave. Although the collective agreement is of higher rank, in this case, the provision in Employee A’s employment contract applies due to the principle of favorability.

Within the same rank, there is no room for the hierarchy or favorability principles. In cases of competition among sources of the same rank, the specialty principle applies, meaning the more specific norm takes precedence over the more general norm, regardless of the chronological order. When no regulation is more specific, the displacement principle or order principle is applied, in which the newer regulation replaces the older one.

Example:

The employment contract grants Employee A 27 days of annual leave, the in-house collective agreement specifies 26 days, and the industry-wide collective agreement specifies 28 days. However, the works agreement prescribes 30 days of leave. The hierarchy of design factors is as follows:

I. Statute: § 3 (1) BUrlG – at least 24 working days, Collective Agreement: 26 or 28 working days Works Agreement: 30 working days Employment Contract: 27 working days II. In resolving competition issues considering the hierarchy and favorability principles alone, Employee A would be entitled to 30 working days of paid leave according to the works agreement. However, the works agreement is invalid due to a violation of § 77 (3) BetrVG.

III. Between the in-house collective agreement and the industry-wide collective agreement, there is competition at the same rank. Consequently, the in-house collective agreement prevails over the industry-wide collective agreement under the specialty principle. There is no room for the application of the principle of favorability. Thus, the collective agreement provides a legal entitlement to 26 working days of leave. Nevertheless, the individual contractual agreement in the employment contract is more favorable, entitling Employee A to 27 working days of paid leave based on the principle of favorability.

4 Individual Labor Law Factors

4.1 European Law

European law is gaining increasing practical significance in labor law, with a distinction between primary and secondary community law.

4.1.1 Primary EU Law

Primary law constitutes the central legal source of European law in the narrower sense. It consists of treaties concluded between the member states. The most important primary legal treaties today are the Treaty on European Union (EU Treaty) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom Treaty) is still valid. Also included in primary law are the protocols attached to these treaties, which regulate specific issues but are legally equivalent to the treaties.

Examples of primary European law provisions with relevance to labor law:

- Article 157 TFEU prohibits not only direct but also indirect discrimination on grounds of sex concerning pay, unless such discrimination is objectively justified and unrelated to sex discrimination. Indirect sex discrimination occurs when a gender-neutral rule results in a considerably larger number of women being affected compared to men, which is primarily the case when part-time employees are treated less favorably in comparison to full-time employees (see also § 4 (1) Part-Time and Fixed-Term Employment Act). In case of a violation of Article 157 (1) TFEU, there is a right to obtain the withheld benefits. According to consistent case law of the ECJ and BAG, there is no claim for overtime supplements due to lack of discrimination against women as defined in Article 157 TFEU if the regular working hours of a full-time employee are not exceeded.

- Article 45 et seq. TFEU guarantee the freedom of movement for workers of the member states. They caused a sensation, especially through the „Bosman“ ruling, which declared invalid the foreign player clauses and transfer rules of football associations. The right to invoke freedom of movement under Article 45 TFEU is excluded in purely „internal“ circumstances because in such cases, it is not EU law but the internal legal system of the member state that is decisive.

- Article 49 et seq. TFEU guarantee the freedom of establishment, while Article 56 et seq. TFEU ensure the freedom to provide services. These provisions have gained practical importance in recent times, particularly due to cross-border employee deployment, the Posted Workers Act, and so-called „wage loyalty“ regulations (awarding contracts only to companies paying the locally agreed wage) in cross-border service provision.

4.1.2 Secondary EU Law

Secondary law (law derived from primary law) comprises legal acts adopted by the institutions of the European Union or the European Atomic Energy Community on the basis of primary law. Secondary law must not conflict with primary law. In the event of a breach of primary law, the European Court of Justice can declare secondary law invalid.

Article 288 TFEU provides for the following legal acts:

- Regulations

- Directives

- Decisions (binding provisions in individual cases)

- Recommendations and opinions (non-legally binding)

EU Regulations, as per Article 288 (2) TFEU, constitute directly applicable law in every member state without the need for national transformation. However, the Council may only adopt EU Regulations based on a specific authorization basis in the TFEU (e.g., Article 46).

EU Directives, according to Article 288 (3) TFEU, are addressed to individual member states and impose an obligation to achieve specific regulatory objectives within a certain period by enacting appropriate legal norms. EU Directives generally only become effective within national law through national legislative action.

Examples of the implementation of EU Directives in national law include:

- The General Equal Treatment Act (AGG), which came into force on August 18, 2006

- § 613a of the German Civil Code (BGB)

- The Proof of Employment Act (NachwG)

- The Occupational Health and Safety Act (Arbeitsschutzgesetz)

- Amendments to the Working Time Act (ArbZG)

The practical importance of anti-discrimination directives is evident, particularly in cases related to the prohibition of discrimination under § 7 (1) AGG, which has replaced the sex-specific discrimination prohibition of § 611a BGB a.F. (former version), women’s quota regulations, access for women to service involving the use of firearms, and the prohibition of discrimination against severely disabled employees under § 81 (2) SGB IX, which refers to the AGG due to the specifics involved.

4.2 Constitutional Law

Labor law, as a protective right for employees, is particularly committed to the social welfare principle of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz), so constitutional law plays a significant practical role in labor law as a legal source subordinate only to EU law. All state or collective legal norms are null and void if they violate the primary constitutional law, especially fundamental rights. Fundamental rights are primarily defensive rights against state power. Therefore, they do not have direct applicability among private law subjects. Nevertheless, fundamental rights indirectly affect private law, particularly in labor law, through their significance in interpreting laws and specifying general clauses and general principles (so-called „indirect third-party effect“ of fundamental rights). However, according to prevailing doctrine, Article 9 (right to form trade unions) constitutes a directly effective fundamental right.

The following fundamental rights are indirectly significant in labor law:

- Article 1 (Human Dignity)

- Article 2 (Freedom of Individual Development)

- Article 2 (Right to Life and Physical Integrity)

- Article 2 (Freedom of the Person)

- Article 3 (Equality Principle)

- Article 3 (Equality of Men and Women)

- Article 4 (Freedom of Belief, Conscience, and Religion)

- Article 5 (Freedom of Expression)

- Article 6 (Protection of Marriage and Family)

- Article 12 (Freedom to Choose Occupation, Workplace, and Vocational Training)

- Article 9 (Freedom of Association)

Example: Right to Personal Integrity

Through the right to personal integrity, labor law protects employees against intrusions into their personal privacy. An employee must, in exceptional cases, accept measures that infringe upon their personal rights when justified by overriding operational interests. Generally, an applicant does not have to disclose prior convictions, especially if they have already been expunged from the Federal Central Register. However, if an employee applies for a position of trust, they must provide information about non-expunged prior convictions that raise doubts about their suitability for the intended position (e.g., prior convictions related to financial or property offenses).

Example: Equality Principle of Article 3 of the Basic Law

In labor law, the general principle of equality of Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law has led to the customary legal concept known as the „equal treatment principle“ or „principle of equal treatment“ (Gleichbehandlungsgrundsatz). The general principle of equality applies directly between the parties to an employment contract. It obligates employers not to treat individuals or groups of employees unfairly. Unequal notice periods for workers and salaried employees are in violation of Article 3 (1) of the Basic Law and are therefore invalid. An employer who provides a Christmas bonus to all employees cannot exclude an individual employee from this benefit. However, an employer may provide lesser benefits to non-union employees who do not fall under a collective agreement due to the absence of union membership. The lower compensation for non-union employees is based on a legitimate reason, as these employees have not submitted to the collective power of the concluding unions.

In labor law, the specific principle of equality of Article 3 (2) of the Basic Law is of particular importance and is also found in other regulatory levels (e.g., General Act on Equal Treatment, AGG). The equality principle of men and women is especially relevant in terms of access to employment. However, a violation of the equal treatment requirement does not grant a disadvantaged employee the right to employment but only an entitlement to compensation for damages.

Example: Freedom of Belief, Conscience, and Religion

If an employee refuses to perform a job duty due to religious reasons, this can justify termination by the employer. However, no other reasonable job alternatives must be available. An employee hired as a „sales assistant“ in a retail store must anticipate receiving work tasks that involve handling alcoholic beverages. If they claim to be religiously hindered from performing tasks contractually required of them, they must inform the employer about the specific religious reasons and indicate which tasks they are unable to perform. If the employer, within the scope of its operational organization, has the opportunity to provide the employee with work that complies with the religious limitations, it must assign this work to the employee (BAG, decision of February 24, 2011, – 2 AZR 636/09).

4.3 Labor Laws

Labor laws are generally federal laws in most cases. Regional variations affecting labor law are mainly found in public holiday regulations and regulations related to educational leave. Deviating from labor law regulations is generally permissible to the advantage of the employee (the so-called principle of favorability). However, laws can only be deviated from to the detriment of the individual employee if the law is dispositiv, i.e., subject to individual agreement. Whether a law is mandatory or dispositiv can usually be determined from the law itself (e.g., § 619 of the German Civil Code, BGB) or must be determined through interpretation, where the protective purpose of the norm is decisive (e.g., the provisions of the Maternity Protection Act and the Protection Against Unfair Dismissal Act are mandatory, as the protection of the persons involved is paramount). Regarding dispositiv norms, a distinction is made between collective bargaining dispositiv norms and party dispositiv norms. Collective bargaining dispositiv norms can be deviated from in collective bargaining agreements, even to the detriment of the employees (e.g., shorter notice periods than the statutory ones can be agreed upon, § 622 (4) BGB). Party dispositiv norms, which can also be deviated from in individual employment contracts to the detriment of the employee, are rare (e.g., § 613, § 616 BGB).

However, if a collective bargaining agreement uses collective bargaining dispositiv norms, in most cases, the less favorable collective agreement can also be adopted in individual employment contracts. By including the collective agreement in the individual contract, the legislative purpose of the law is met because the regulation was negotiated by the collective bargaining parties (e.g., § 622 (4) sentence 2 BGB). This ensures the balance of power between the negotiating parties.

Example: The Collective Agreement for the Hotel and Restaurant Industry in State X prescribes a notice period of three days during a one-month probationary period. This regulation deviates from the statutory notice period during the probationary period stipulated in § 622 (3) BGB, to the detriment of the employee, and can only be agreed upon by the parties to the collective bargaining agreement, as per § 622 (4) sentence 1 BGB. In the scope of the collective agreement, non-union employers can also adopt this regulation in individual employment contracts, as stipulated in § 622 (4) sentence 2 BGB. However, they must adopt the entire regulations and not just parts of it.

4.4 The Collective Bargaining Agreement

A collective bargaining agreement is a contract between a trade union and, on the other side, an employers‘ association or an individual employer. This contract regulates the working conditions of the employment contracts covered by it. According to § 1 (1) of the Collective Bargaining Agreement Act (Tarifvertragsgesetz, TVG), it states:

§ 1 Content and Form of the Collective Agreement

(1) The collective agreement regulates the rights and obligations of the collective agreement parties and contains legal provisions that can regulate the content, conclusion, and termination of employment relationships, as well as operational and works constitution law matters.

While collective agreements on the employer side can be concluded by both an employers‘ association and an individual employer, on the employee side, only trade unions can conclude collective agreements. For example, a works council or a group of employees cannot conclude collective agreements. They are not „tariffähig.“

Depending on who has concluded a collective agreement on the employer side, a distinction is made between a mandatory collective agreement (= sector-wide collective agreement) and a voluntary collective agreement (= company-specific collective agreement). The sector-wide collective agreement is concluded by the employers‘ association. It covers all businesses whose owners are members of the employers‘ association. The company-specific collective agreement, on the other hand, is concluded by an individual employer. It is only valid for the operations of this employer.

There are three different reasons why a collective agreement applies to an employment relationship:

- The collective agreement applies because the employee is a member of the trade union that has concluded the collective agreement, and at the same time, the employer is bound by the collective agreement because they are either a member of the employers‘ association that concluded the collective agreement (in the case of a sector-wide collective agreement) or themselves a party to the collective agreement (in the case of a company-specific collective agreement). This is called the „collective agreement effect.“

- The collective agreement applies because the employee and the employer have agreed in the employment contract that a specific collective agreement should apply to the employment relationship. This is known as the application of the collective agreement through individual contractual agreement. In this case, it does not matter whether the employee is a member of a trade union or whether the employer is bound by the collective agreement, i.e., whether they are a member of an employers‘ association or have concluded a collective agreement.

- The collective agreement is declared universally binding by the Federal Minister of Labor and Social Affairs. This is known as the application of the collective agreement through universal binding. Under certain conditions, the Federal Minister can take this measure when the „normal“ application of the collective agreement (the first possibility) is insufficient to ensure uniform working conditions in a specific industry and adequate protection for employees. In this case as well, it does not matter whether the employee is a member of a trade union or whether the employer is bound by the collective agreement.

When considering whether the norms of a collective agreement can be deviated from in an individual employment contract, it depends on which of the above-mentioned three reasons the collective agreement is applicable to the employment contract in the first place.

In the first scenario (collective agreement effect), deviation from a collective agreement through the employment contract is generally not possible because the collective agreement directly and mandatorily applies to the employment relationship. A deviation is permissible in exceptional cases if the collective agreement allows for such deviation (the so-called opening clause), or if the deviation is provided in a regulation that is more favorable to the employee than the collective agreement.

These principles also apply when the collective agreement is universally binding (third possibility). Employees can only deviate from a collectively agreed upon universally binding collective agreement if such deviation is allowed in the collective agreement, or if the deviation is more favorable to the affected employee than the collective agreement from which they are deviating.

However, things are different when the collective agreement applies through an individual contractual agreement (second possibility). In this case, your employer cannot easily deviate from the collective agreement because that would violate the employment contract. Nevertheless, the employer can modify the employment contract in agreement with the employee to deviate from the collective agreement. The employer also has the option to free themselves from the collective agreement by issuing a change notice. The change notice first terminates the existing employment relationship (and thus the application of the collective agreement). If, in the next step, there is an agreement on the continuation of the employment relationship under changed conditions – without the collective agreement – then the collective agreement has effectively been excluded through the change notice or change agreement.

As mentioned earlier, the exclusion of the collective agreement by the employer must be in compliance with the law. Employees who enjoy protection against dismissal can accept the offer associated with the change notice with a reservation and have the legality of the contract change reviewed by the labor court.

4.5 The Works Agreement (Betriebsvereinbarung)

Another peculiarity in German labor law is the works agreement (Betriebsvereinbarung). A works agreement is an agreement between an employer and a works council (Betriebsrat) that regulates and shapes the company’s organization, co-determination rights, and individual relationships between the employer and employees. Works agreements have direct and mandatory legal effect (§ 77 Abs. 4 S. 1 BetrVG), making them the „laws of the company.“

Works agreements can be categorized as either mandatory or voluntary, depending on the matters they address. Mandatory works agreements are those that deal with issues where the works council has „genuine“ co-determination rights. This occurs when disputes between the employer and the works council about co-determination rights require a decision by the conciliation board (Einigungsstelle). On the other hand, voluntary works agreements allow for comprehensive regulation since the boundaries between social, personal, and economic co-determination are often fluid (Federal Labor Court (BAG) ruling of 07.11.1989, DB 90, 1724).

The scope of works agreements is limited by the primacy of the law and collective agreements, as set forth in §§ 77 Abs. 3 and 87 Abs. 1 BetrVG. According to the provision lock (Regelungssperre) in § 77 Abs. 3 S. 1 BetrVG, issues such as wages and other working conditions that are typically regulated by collective agreements cannot be the subject of a works agreement. However, this does not apply when § 77 Abs. 3 S. 2 BetrVG permits the conclusion of supplementary works agreements if a collective agreement explicitly allows it (known as an opening clause or Öffnungsklausel).

Works agreements should be distinguished from an informal agreement, known as a „regelungsabrede,“ between an employer and an employee concerning company issues. Unlike works agreements, a regelungsabrede does not have the same regulatory effect (BAG from 14.02.1991, DB 91, 1990).

4.6 The Employment Contract

An employment contract (Arbeitsvertrag) under German law is an agreement establishing a private-law contractual relationship for remunerated and personal service provision. Originally, the employment contract was not explicitly defined in the German Civil Code (BGB). It was always considered a subcategory of the service contract under § 611 BGB, without being explicitly mentioned there.

However, the formulation „In the case of an employment relationship that is not an employment contract“ in § 621 BGB (notice periods in service contracts) and the regulation in § 622 BGB (notice periods in employment contracts) made it clear that the legislator distinguishes between the (free and general) service contract and the (specific) employment contract.

With the inclusion of § 611a BGB, the legislator has now clarified that the service contract continues to be regulated under § 611 BGB, while the specific provision of § 611a BGB applies to employment contracts.

Nevertheless, the following still holds:

Every employment contract is a service contract, but not every service contract is an employment contract.

The distinction between an employment relationship and a general service contract is important because the rights and obligations of the parties differ based on the legal classification.

The most significant difference between an employment contract and a service contract is that the service contract is based on a relationship between two equal partners, whereas an employment contract establishes an employer-employee relationship.

An employer-employee relationship is characterized by the employer having a position of power over the employee. This position of power includes the right to issue instructions (§ 106 GewO, § 611a BGB), demand specific work results, and control the work process.

In contrast to a free service relationship, the employment relationship established by the employment contract is marked by the employee’s personal dependence on the employer. The employee is essentially unable to determine their own activities and working hours, as a self-employed individual can (§ 84 Abs. 1 sentence 2 HGB). The employee is instead integrated into the employer’s work organization and is typically subject to the employer’s instructions regarding the content, execution, time, duration, and location of the work.

Due to this dependency, special protection is required. Therefore, labor law is often referred to as the special law or protective law for employees.

Employees are subject to the special protective regulations of labor law, which do not apply to the self-employed, who „can essentially determine their activities and working hours freely.“

The employment contract is, therefore, a special form of the service contract, which is why specific provisions of the employment contract, in addition to the general service contract regulations, apply. The provisions of the employment contract take precedence over the general service contract provisions.

Based on the employment contract, the employee is obliged to provide the contractual work performance. In return, the employer must provide compensation. The amount of compensation is determined by the agreement in the employment contract or an applicable collective agreement. If no compensation is agreed upon, the usual compensation for comparable work must be paid, as per § 612 BGB. Additionally, other obligations can be specified in the employment contract. When the content, time, and place of the work are not explicitly defined in the employment contract, their determination falls under the employer’s right of direction, which they can exercise reasonably.

As a whole, the employment relationship is flanked by labor law regulations (protection against dismissal, limitation of fixed-term contracts, labor protection, working time laws, works constitution laws, etc.). These regulations partially limit the discretion of the contracting parties. This is the result of the structural power imbalance between the contracting parties and the social-state intention that is based on the fact that the majority of the population earns their livelihood through dependent work.

Employment contracts, in general, do not require a specific form. They can be formed both in writing and orally, through a handshake, or even by simply commencing the work. Nevertheless, in terms of evidence, entering into a written employment contract is generally recommended. There is a mandatory legal requirement for written form when concluding a fixed-term employment contract. A violation of this requirement has far-reaching consequences. To protect the employee, and often to the dismay of the employer, the employment contract is not null and void but is considered concluded for an indefinite period under the law (as explained in relation to fixed-term employment contracts). Similarly, valid collective agreements may require the written conclusion of an employment contract. However, violations of this requirement typically do not lead to the invalidity of the employment contract, as they are usually of a declaratory nature.

If employment contract terms are pre-formulated for a large number of contracts, they generally fall under the law of general terms and conditions as per §§ 305 et seq. BGB.

4.6.1 The Proof of Employment Law (Nachweisgesetz)

Even when no written employment contract is established, particular attention should be paid to the Proof of Employment Law (Nachweisgesetz).

The Proof of Employment Law itself is not new. However, in practice, it wasn’t given much importance because a violation of the employer’s obligation to record the actual contractual conditions was previously without sanctions.

This has now changed abruptly.

In order to implement the Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions in the European Union (EU 2019/1152, „EU Transparency Directive“), the German legislature amended the Proof of Employment Law (NachwG) as of August 1, 2022.

The goal is to make employment contracts more transparent, which is why far more details must now be put in writing than before.

Additionally, for the first time, there is now a possibility of sanctions for a violation, specifically a fine of up to €2,000. A violation is now treated as an administrative offense.

In the case of a violation of the Proof of Employment Law, the employment contract remains valid, but it can be costly for the employer. As a result, it can be expected that employers will increasingly strive to comply with the Proof of Employment Law’s requirements in the future.

The previous obligations of the employer included:

The employer had to put the most important contractual conditions in writing and hand them to the employee in writing within one month after the start of the employment relationship. This included the following points:

- Names and addresses of the contracting parties

- Commencement of the employment relationship

- Duration of the employment relationship in the case of fixed-term contracts

- Place of work

- Description of the job or activity

- Composition and amount of the remuneration

- Working hours

- Duration of annual leave

- Notice periods

- A general reference to collective agreements, works agreements, and service agreements applicable to the employment relationship.

From August 1, 2022, the following additional points must also be documented in writing:

- End date of the employment relationship

- If applicable, the employee’s choice of workplace

- If agreed upon, the duration of the probationary period

- Composition and amount of the remuneration, including compensation for overtime, surcharges, allowances, bonuses, and special payments, each to be stated separately along with the due dates and method of payment

- The agreed-upon working hours, rest breaks, and rest periods, and, in the case of shift work, the shift system, shift rotation, and requirements for shift changes

- If agreed upon, the possibility of ordering overtime and its conditions

- Any entitlement to employer-provided further training

- If the employer promises the employee a company pension through a pension provider, the name and address of this pension provider; the obligation to provide proof is waived if the pension provider is obliged to provide this information.

- The procedure to be followed when terminating the employment relationship by the employer and employee, at the very least the requirement for written notice and the deadlines for giving notice, as well as the deadline for bringing a legal action challenging the termination; § 7 of the Protection Against Unfair Dismissal Act is also applicable to the deadline for bringing a legal action challenging the termination in the event of an incomplete proof of notice.

These new obligations only apply to new hires from August 1, 2022. Unlike the previous regulation, the written record containing the information about the names and addresses of the contracting parties, the remuneration and its composition, and working hours must be available to the employee on the first day of work. The remaining records must be provided within seven calendar days at the latest.

Employees hired before August 1, 2022, only need to be informed in writing about their essential employment conditions if they request it from the employer. Then, a deadline of seven days applies. Information about vacation, company pensions, mandatory further training, the termination procedure, and applicable collective agreements must be made available within one month at the latest.

4.6.2 General Terms of Employment

General terms of employment refer to the standard employment contracts unilaterally established by the employer and used as the basis for individual employment contracts. They also include so-called general promises or commitments made by the employer to the workforce. With these commitments, employees acquire individual contractual rights to the promised benefits, which they can either accept or reject. An explicit acceptance by each employee is not necessary according to § 151 of the German Civil Code (BGB).

In the context of labor law, it is understood that general promises can only relate to provisions that favor the employee. In the relationship between a general promise and a (deviating) works agreement, the principle of favorability applies. A general promise results in the creation of genuine contractual rights for employees regarding the promised benefits, which are to be treated in the same way as claims that are documented in a written contract. Without a voluntary or revocation clause, the employer can no longer unilaterally withdraw the obligation to provide these benefits.

If an employer wishes to revoke employees‘ entitlement under a general promise, they can generally only do so by entering into corresponding modification agreements with the employees or by issuing effective amendment notices (Änderungskündigungen).

4.6.3 Company Practice

Company practice is not governed by statute; it was developed by labor courts. Company practice refers to the regular repetition of specific employer behaviors from which employees can conclude that they will be granted a benefit or concession over the long term. Company practice thus leads to an improvement in the employee’s contractual rights and therefore to a substantive change in the employment contract. Company practice can give rise to various claims, often involving payment claims.

For example:

An employer pays its employees a Christmas bonus equal to one month’s salary in 2018, 2019, and 2020, even though there is no obligation to do so. In 2021, due to poor economic conditions, the employer decides not to pay the Christmas bonus. Meanwhile, employees have gained a legally enforceable claim to an annual Christmas bonus equal to one month’s salary due to company practice.

A requirement for company practice is that the entitlement is neither regulated by collective nor individual law (BAG 24.11.2004 – 10 AZR 202/04). In addition, company practice must apply to a significant number of employees or at least to a distinct group of employees. The concept of company practice contains a collective element. The mere provision of benefits to individual employees does not, on the principles of company practice, imply a binding intent by the employer to extend the benefits to all employees or at least to all employees in a distinguishable group (BAG 11.04.2006 – 9 AZR 500/05). If an employee’s entitlement is contingent on this requirement, an individual employment contract may result in an implied agreement (BAG 21.04.2010 – 10 AZR 163/09).

There is no universally applicable rule specifying at what point an employee can expect that they will receive a benefit once they fulfill the criteria. The three-time repetition principle, where an obligation becomes binding after being granted three times without reservation, was developed for bonuses paid annually to the entire workforce. For other benefits, the assessment should be based on the type, duration, and frequency of the benefits. The evaluation of the relationship between the number of repetitions and the duration of the practice should consider the nature and content of the benefits. Higher requirements are imposed on the number of repetitions for less significant benefits than for more important ones (BAG 28.05.2008 – 10 AZR 274/07).

An entitlement from company practice can also arise when payments made to a group of employees are not disclosed to other employees and are not generally communicated within the company (BAG 17.11.2009 – 9 AZR 765/08). The establishment of company practice is not precluded if the employment contract contains a (simple) written form clause requiring any changes to the contract to be in writing. According to a decision by the Federal Labor Court, even a double written form clause („Changes to the employment contract must be in writing. This also applies to this written form clause“) cannot avoid company practice (BAG 20.05.2008 – 9 AZR 382/07, NJW 2009, 316).

However, if the employer made the payment as „voluntary,“ with varying amounts, or with the disclaimer „without acknowledging any legal obligation,“ the employee could not expect it to continue.

Nevertheless, high standards are set for the voluntary reservation clause.

For example:

An employer paid a Christmas bonus equal to one month’s gross earnings each year from 2002 to 2007, without explicitly stating a reservation at the time of payment. In 2008, the company refused to make the special payment due to the economic crisis. It relied on the following clause in the employment contract: „To the extent that the employer grants benefits not required by law or collective bargaining agreement, such as bonuses, allowances, vacation pay, gratuities, and Christmas bonuses, they are provided voluntarily and without any legal obligation. They are, therefore, revocable at any time without special notice.“ The Federal Labor Court found the contract clause to be unclear and ambiguous. It could also be understood to mean that the employer wanted to voluntarily commit to providing the benefit. Furthermore, revoking the benefit as reserved would require that a claim had been established in the first place. The uncertainties in the provision were detrimental to the employer. Since the employer had not explicitly referred to the voluntary nature of the payment in previous Christmas bonus payments, the practice of company practice remained in effect in the following years, despite the unclear contractual provision (BAG 08.12.2010 – 10 AZR 671/09).

Under the previous jurisprudence of the Federal Labor Court, company practice that had already arisen could also be changed by a so-called „negative company practice.“ Negative company practice occurs when the employer indicates over a period of three years that it intends to treat company practice differently from before. In this case, the old company practice was mutually changed to reflect the new approach if employees did not object to the new practice during this three-year period. However, the Federal Labor Court has now ruled, in a departure from its previous case law, that three-time unopposed acceptance of a bonus paid by the employer under a reservation of voluntariness can no longer lead to the loss of a contractual entitlement established through company practice due to the three-year limitation clause under § 308 No. 5 of the German Civil Code (BGB) (BAG, March 18, 2009 – 10 AZR 281/08).

If an entitlement has arisen from company practice, it exists alongside other conditions in the employment contract. It can no longer be unilaterally withdrawn or changed. Only through an amendment notice (Änderungskündigung) can the established company practice be eliminated, following the principles of § 2 of the German Protection Against Unfair Dismissal Act (KSchG). The termination of the practice of company practice, like any other termination, must be justified on social grounds.

4.6.4 The Principle of Equal Treatment in Labor Law

The principle of equal treatment in labor law is a principle developed by case law and is not generally governed by statutory law. The general principle of equal treatment in labor law is derived from the constitutional principle of equal treatment in Article 3 of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz, GG) in Germany. Specific forms of the equal treatment principle are, however, often found in the law, such as in Sections 7, 11, 12 of the General Act on Equal Treatment (Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz, AGG), § 612a of the German Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, BGB), § 75 of the Works Constitution Act (Betriebsverfassungsgesetz, BetrVG), and § 4(1) of the Part-Time and Fixed-Term Employment Act (Teilzeit- und Befristungsgesetz, TzBfG).

The principle of equal treatment requires the employer to treat employees or groups of employees who are in a comparable situation equally when applying a self-imposed rule. It prohibits arbitrary discrimination against individual employees within the groups and creating groups for reasons unrelated to work (BAG 13.09.2006 – 4 AZR 236/05). When the principle of equal treatment applies, it has a claim-establishing effect, meaning that, like with company practice, it becomes part of the employment relationship.

The reasons for differential treatment must be disclosed by the employer, especially when the employee requests better treatment. If these reasons are only presented during a lawsuit, they will not be taken into account.